Captain Kay

Lathom House, near Wigan, was the principal residence in Lancashire of the Earl of Derby. Described by one historian as vain, silly and narrow minded, the Earl was commander of the Royalist forces in Lancashire during the Civil War. Regarding Lancashire as his fiefdom, he viewed any support for the Parliamentary cause as an insult to the House of Stanley, and his high handed and brutal methods caused as much consternation among his supporters as they did alarm among his opponents.

At the start of the war, Manchester was the only fortified town in Lancashire in Parliamentary hands, but the forces of Parliament made progress and by 1644 the situation was becoming dire. In 1644, Prince Rupert marched into the country to restore order. Attacking and sacking Bolton – known as the Geneva of the North because of the Puritan nature of its inhabitants – he crossed into Yorkshire to relieve the siege of York, only to meet defeat at Marston Moor. Lancashire was effectively lost to the Royalist cause. It was for his treatment of prisoners in general, and his conduct at the sack of Bolton in particular, that the Earl of Derby was executed in Bolton in 1651.

While he was rampaging about the countryside, the Earl had entrusted the defence of Lathom to his formidable wife. In February 1644, Sir Thomas Fairfax invested the house and the first siege began. She defied his call to surrender:

“… To seconde and confirme her answer, the nexte day, beinge Tuesday, 100d foote, com’anded by Captain Farmor, a Scotchman, a faithfull and gallant souldier, with Lieut. Brethergh ready to second him in any service, and some 12 horse, our whole cavallerie, com’anded by Lieut. Kay, sallied out upon the enemy” [CS-1]

Contemporary references to Captain Kay are rare. Apart from the above quote, we’ve found only two other mentions of him in documents from the period. There is mention of one Hodges, taken prisoner “… in 1644 when Prince Rupert was in the county … and deponent said that about three months after that there were three melts of malt taken from Hodges, which deponent procured him again. The malt was taken by Captain Kaye and his men, as he had heard.” [LCRS Vol 24], while the registers of St Elphins, Warrington recorded the burial on 20th July 1644 of “William Mullins, a souldier to Capptain Kay” [LPRS Vol 70].

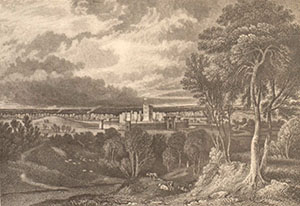

Over the centuries, the two sieges have become the stuff of legend. John Roby, in his ‘Traditions of Lancashire’ (1829), wrote a fanciful account of the first siege, while Captain Kay features in the novel ‘The Changeling of Brandlesholme’ by Roma White (whose real name was Blanche Oram; she was a descendant of John Kay the inventor). The picture shown here is a reconstruction of the house in John Roby’s book.

Over the centuries, the two sieges have become the stuff of legend. John Roby, in his ‘Traditions of Lancashire’ (1829), wrote a fanciful account of the first siege, while Captain Kay features in the novel ‘The Changeling of Brandlesholme’ by Roma White (whose real name was Blanche Oram; she was a descendant of John Kay the inventor). The picture shown here is a reconstruction of the house in John Roby’s book.

The indomitable Countess held her own, immobilising a large part of Lancashire’s Parliamentary forces for several months until arrival of Prince Rupert. After Rupert’s defeat at Marston Moor, the second siege began, but this time without the Countess who had joined her husband in the Isle of Man. After a long and heroic resistance, the garrison finally capitulated in December 1645.

“When the house was given up, there were but two hundred and nine foot soldiers in it, and of all their horse but five left alive, the rest being all eaten up. The common soldiers were all discharged, as before, but their gallant and brave commanders were all made close prisoners, and so continued a long time after.”

That quote comes from Seacombe’s History of the House of Stanley (1741). He gave more details of the siege, writing:

“The new Governor, Colonel Rosthern, was neither wanting in care or diligence, nor in any other good offices for the supply of the garrison with provisions and all other necessaries for sustaining a siege … The Governor disposed the soldiers to their respective officers. Commanders of horse were Major Munday and Captain Kay … Although none of them (except Captain Farmer, Major Munday, and Captain Kay) were bred in a military way, unless as a county militia, yet it may with modesty and justice be asserted that no officers of any degree bred in the School of Mars, or elsewhere, ever shewed more conduct, courage and magnaminity, than those brave and worthy gentlemen … Major Munday and Captain Kay, who commanded the horse, were certainly in no way inferior to any officers of horse in the King’s arm …

… Captain Kay also challenged by a trumpet from the enemy, to fight hand to hand on horseback with Captain Asmall, a Captain of the adverse party, he accepted the challenge: both troops met in the park, and stood aloof, whilst the captains fought single. In the engagement, Captain Asmall having discharged his pistols at Captain Kay, without much effect, Kay immediately rode up to him, and thrust him through the neck with his javelin, on which he fell down dead from his horse; Captain Kay alighting, took him up in the face of his troop, and flung him upon his own horse, and brought him into the house; upon which Captain Kay’s Lieutenant offered to fight Asmall’s Lieutenant, hand to hand, or troop to troop, but they refused the offer, and fled to their main body.”

Seacombe’s tales of derring-do are not corroborated by the contemporary sources to be found in the Civil War Tracts, and give the appearance of being grossly over-inflated. For example, in one engagement he claimed many hundreds of Parliamentary dead for the loss of just twelve defenders. It must be remembered that he was writing some ninety years after the event, and his history was aimed at the Stanleys – he was at the time their steward – so his work must be taken with a large pinch of salt. He said his account was based on that of Archdeacon Rutter, who was present at the siege and would hardly have been impartial; that said, his work shows no more bias than many of the contemporary tracts, which were often works of blatant propaganda rather than judiciously balanced factual reports.

Colonel Edward Rawsthorn, who had been appointed governor of the house at Prince Rupert’s particular request, died in 1646 shortly after the siege ended; he was a son in law of John Greenhalgh of Brandlesholme Hall in Bury. Another son in law, Richard Holt of Ashworth in Middleton, was also at the siege, returning home “dangerously sick” [LCRS Vol 29] and in severe financial straits. John Greenhalgh himself acted as the Earl of Derby’s ‘captain’ (governor) in the Isle of Man throughout the war, and died there in 1651 from wounds received at the Battle of Worcester. Major Munday, after his release, rejoined the Royalist forces, but was recaptured and executed in Lancaster in 1649 [WH].

There was another Kay at the siege, but on the Parliamentary side, as is shown by the following letter to the Sequestration Commission “Wee were imployed as Commanders and Officers in ye late Leagre att Lathome, & in that tyme were well acquainted with ye bearer hereof, Mr Alexander Breres, who in the tyme of that Service did shew unto us a very civill and friendly respect, and was pleased of his owne acord and good will to afford both unto Officers and Souldiers more free Quarter then anie Gentleman about that place. And for anie thing wee knowe to ye contrary, Wee verily believe that the said Mr Breres to bee a very honest man, and never to have carried anie Armes against ye Parlt etc (signed among others) George Key” [LCRS Vol 24]. The identity of this man is unknown, except that he was a Lancastrian, but he is noteworthy as being one of the few people of plebian origin who attained the rank of colonel on either side [GC].

Tradition has always maintained that Captain Kay was from Cobhouse, a property in Walmersley in Bury. What were reputed to be his sword and dagger, together with a supposed portrait of him, were in the possession of the family at the end of the nineteenth century [KK]. The picture shown here is of an engraving believed to be taken from that portrait. Although it was already known that he was William Kay of Cobhouse [CS-2], it was William Hewitson who firmly established his identity in 1910.

Tradition has always maintained that Captain Kay was from Cobhouse, a property in Walmersley in Bury. What were reputed to be his sword and dagger, together with a supposed portrait of him, were in the possession of the family at the end of the nineteenth century [KK]. The picture shown here is of an engraving believed to be taken from that portrait. Although it was already known that he was William Kay of Cobhouse [CS-2], it was William Hewitson who firmly established his identity in 1910.

Wills, leases and the parish registers very clearly identify five generations of Kays at Cobhouse in the 17th century. First there was William who died in 1588. His son Robert was married three times and left 7 children, all minors at the time of his death in 1612. Then there was Robert’s son William who was born in 1599, followed by his son Robert who was born in 1619. Finally, there was a third William who died unmarried and childless in 1717/8. Canon Raines wrote of old Cobhouse “Over a window of the older part there is cut in stone ‘W.K.D.1631’, and over another window in stone ‘R.K.E.1662’“, referring to the marriages of William to Dorothy Barlow and Robert to Elizabeth Low (they were actually married in 1616 and 1643 respectively). William Hewitson recorded a gravestone in Bury Churchyard where were buried “Doritie Kay of Cobhouse who dyed the 16th of January 1688 Aged 94”, “Elisabeth wife of Robert Kay late of Cobhouse who departed this Life ye 18th day of November 1709 in the 85th year of her Age” and “William Kay their Son who departed this Life the 15th day of January Anno Dom: 1717 and in the 73rd year of his age” [WH].

So why weren’t that second William and his son Robert in that grave and why don’t we have wills for them? The answer is that they both died in prison. In the Lancaster parish registers, there is an entry for the death on 8th March 1670/1 of “Capt: William Kaye a prisoner for debt” [LPRS Vol 32] while the Midsummer Quarter Sessions in Manchester in 1670 have a plea from “Capt William Kay now prissonr in the Castle of Lancaster” [LA-1].

“That your poore petionr haveing beene a prissonr within the said Castle, for the space of a yeare or thereabouts, and haveing noe maintenance neither from his Relations nor off his Estate, by reason of the Combination and unjust dealings of mr Tildesley and my most unnatural Sonn, whereby your petionr is likely to perish through want of releese, being near to ffourescore yeares of age“.

He was in prison and penniless and was pleading for help that he wasn’t getting from home. At the bottom is noted “To allow unto him ijs a weeke“.

After the war, the Earl of Derby’s lands were confiscated and put up for sale. In a survey of those lands conducted in 1652, we find that Cobhouse had been assigned to Robert by William [LA-2] (see note). However William must still have been alive, because in 1664 he renewed a lease for 40 acres of land (on that lease he described himself as a ‘gentleman’) [LA-3], and it is his name that appeared in the Hearth Tax assessments on 1663 and 1664 [PRO]. He no doubt found it wise to maintain a low profile after his part at Lathom, only surfacing again after the Restoration. There was probably a hefty fine to pay as well, and earlier wills suggest that Cobhouse finances were already unstable even before the war – they were rich in property but poor in cash [LA-4]. We don’t know who Mr Tildesley was, but it does seem that Robert, now in possession of Cobhouse, was happy to leave his father to rot.

Did Robert, left to run Cobhouse while his father went off to the wars, feel the time had come for revenge? Were his allegiances towards Parliament? It would not have been the only time that happened – the Earl of Derby’s eldest son joined the Parliamentary side and added insult to injury by marrying against his father and the King’s wishes [LA-5] (see note). But Robert did not enjoy his success for long. In a local law suit in 1687, a witness stated that “Robert Kay, in his latter days, was carried by bailiffs to the common jail at Lancaster for debt, and died there” [WH]. That actually happened ten years earlier, because in 1677 Robert too was forced to plead for support [LA-6]. On 6th April 1685, the Lancaster registers recorded the death of “Rob: Kay a prisoner” [LPRS Vol 32].

There is still so much we don’t know about Captain Kay. Did he really have that military experience that Seacombe claimed? And what did go on between him and his son? But this romantic Cavalier stands high among the legends of the Kay family.

From the copy of the Earl's will, dated 1st August 1651, in which he disinherited his son and left all his possessions to the King:

"this by reason of my just fence against Charles, my eldest son, for his disobedience to his Matie in ye matter of his marriage and for his going to joyne the rebells of England at this tyme to the great grief of his parents, by wch he hath brought a staine upon his blood if he were permitted to inherit, but this by his Mats goodness may be prevented"

There is an anomaly here about William's age. The Particulars give his age as 52 in 1652, which would have him born about 1599. But in his plea to the Manchester Quarter Sessions in 1670, he said he was nearly 80, which would have him born not long after 1590. William's father Robert died in 1612; his will, dated 17th October 1612, has badly deteriorated, but from it we can deduce that Robert had been married three times, and left seven children, all minors at his death.

The Bury Parish Registers have two possible entries for the birth of a William son of Robert Kay from that time, one dated 17th March 1592/3 and the other 13th June 1596; neither give the father's location. The first of these ties in with William's age as given on the plea, the second does not match either of them. Ages given on that survey were not always correct - William was not around at the time to give his age, and there is an instance for another family where it stated the father was ten years older than his son! Bearing in mind also the likely time frame into which a man can pack three marriages and seven children, it seems probably that William was born in 1592/3 and that the age given on the survey was wrong.